You have an idea for a children’s story but aren’t sure how to get it started.

What’s the first step?

Is there a first step?

Is there a step-by-step procedure?

What’s involved?

There are lots of questions that may come up for new writers, but there’s really no ‘for every writer’ answer.

What will work for one writer may not work for another. What may feel comfortable for one writer may not feel comfortable for another.

But with that said, there are several things that every new writer should know about before jumping in. Those things are the elements of a story.

1. The plot.

Sometimes, the plot isn’t the first thing that starts a story. It’s usually an idea for a story.

Once you have the idea, think about how it can evolve, bringing the main character (protagonist) through obstacles to reach his goal. That’s your plot.

In the chapter book/simple middle-grade book Walking Through Walls, the main character, Wang, wants to become rich and powerful; this is the goal. How he goes about achieving it (his struggles) and the resolution is the plot.

Plot also involves having the character grow in some way through the process of reaching his goal.

Another essential plot element is to have a beginning, middle, and end to the story. And it needs to be easily understandable – it needs to make sense.

As a children’s ghostwriter, I sometimes find that some new authors don’t realize that what they know about their story may not be clearly translated onto the page for the reader.

If you’re not sure whether you’re missing the clarity mark, have someone read the story and let you know if they had to pause anywhere or got lost somewhere.

2. The story structure

This is the element of writing your children’s story where you make a number of decisions:

A. How will you begin the story?

It’s recommended to start your story with action. Let the reader get immediately engaged and involved.

B. Should you write it in first-person or third-person?

For a quick example of these two point of views (POVs):

-I went to the store. (The main character is telling the story. The first-person pronoun is ‘I.’)

-He went to the story. (A narrator is telling the story. This is third-person, and the pronoun is ‘he or she … or it.’)

Note: There are other POVs, but these two are the most popular, third-person being more popular than first-person.

C. What tense will you use for your story: present tense or past tense.

Here are two examples:

– I wish I can go to the park. (Present tense – it’s happening here and now.)

– I wished I could go to the park. (Past tense – the story has already happened.)

Once you choose a tense, you must stick with it throughout the story.

Another aspect of POV is that there should be only one main character, the protagonist, for children’s books through simple middle grade. The story is told through this character’s eyes (viewpoint).

3. The characters.

The main character:

Your story will need a main character around whom the story revolves.

It’s important to make this character life-like. Give the character depth and personality. The character should have good qualities along with a flaw or two. And bring this character to life as soon as he enters the stage.

Make the main character three-dimensional.

Secondary characters:

The story should also have secondary characters. These characters go with the main character through his journey. They can be supportive and even unintentionally cause problems.

For a children’s chapter book or simple middle grade, it’d be a good idea to have one or two (at the most) secondary characters. Children’s books should be easy to follow along with. Too many characters can complicate things – like too many cooks in the kitchen.

Think of Robin to Batman or Dr. Watson to Sherlock Holmes as secondary characters. There are even Ron and Hermione to Harry Potter.

Tertiary characters:

These characters appear in the story for a short period, a scene or two. They’re there for a specific purpose (to move the story forward), but aside from that, the reader doesn’t know much about them.

An example of this would be from Walking Through Walls. The main character, Wang, hit his foot with the broad side of an ax. He was in excruciating pain and called out for help from a fellow student.

The student, not named, explained that he couldn’t offer help. They were to fend for themselves. If they couldn’t do that, they couldn’t help others.

That was the only mention of this character, but it was an important scene. It showed Wang and the reader how things worked there.

These are three of the top types of characters. For a complete list, visit: https://www.writerscookbook.com/character-types-story/

For information on supporting characters, check out https://karencioffiwritingforchildren.com/2020/06/21/supporting-characters-and-your-story/

Getting to know your characters:

Many experienced writers say you should get to know each of your characters before you start your story.

This is a good idea because it gives you foresight into what a character may or may not do. You will know how that character will react in certain situations and what drives the character. It provides a comfort level for most writers. It’s like having a well-outlined story before actually starting the first draft.

Other writers are pantsers. They work from a thin outline, if any at all, and the characters unveil themselves as the writer writes the story.

I work with outlines, but I’m also a pantser.

I’ll start a story without knowing a thing about the main character or any other character. My typing fingers unveil it all.

On the flip side, as I mentioned, there is an element of comfort in having an outline. Even if you don’t have all the details on each character, you know where the story starts, how it will rise to its climax, and how it will be resolved. All you do is fill in the details.

4. The setting.

The setting is time and location. It’s where the story takes place and its period. It’s the main character’s surroundings.

In Walking Through Walls, the setting is 16th-century China.

To create a realistic setting, if it’s not your present area, you need to do research. Readers want to be absorbed in a story; they want to know that what they’re reading is based on facts, even if it’s fiction.

If it’s a science fiction or a fantasy story, you will need to create your own world. But, be sure it can be understood and is believable.

Speaking of setting and how it can play a crucial part in your story, Wang was 12 years old when he went on his journey to become rich and powerful. He left his family to do this.

This would be unheard of and unrealistic in a present-day setting. But in 16th-century China, it was certainly plausible.

5. Conflict.

Your plot revolves around the story conflict. The conflict provides tension.

Conflicts can be internal or external. They can be caused by the antagonist (bad guy), emotional turmoil, a personal challenge, a physical handicap, troubled relationships, the elements, or others.

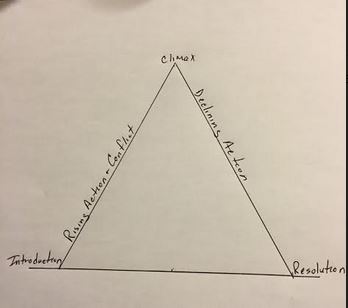

Be sure to make your conflict rise to a peak (the climax) – think of a pyramid.

At the peak, the conflict lessens on its way down the other side, toward the bottom to a resolution.

A great example of conflict is Toy Story 2. The main characters (Woody and Buzz) make several attempts to overcome their obstacles. They try, they fail. They try and fail a couple of more times before they finally succeed.

This is an excellent example of conflict because you don’t want the main character to succeed on the first try. You want to see the character struggle before she finally gets down the other side of the pyramid to resolution.

6. The resolution.

The resolution comes after the main character descends from the story’s climax, from the peak of the pyramid. On the way down the pyramid, the story gets wrapped up. At the bottom of the pyramid is the resolution.

In children’s stories, the main character becomes the hero in the resolution. The character has overcome the obstacles and figured out how to reach the goal with a triumphant conclusion.

It’s important in picture books through simple middle grade for the main character to solve his problem independently or with minimal help. Adults shouldn’t be a focal point in the story; they should have minimal influence and air-time if they’re in the story.

This part of the story should have all loose ends neatly tied up.

Don’t leave the reader wondering what happened to the secondary character, Pete, after he took a wrong turn in the next to last chapter. If something is mentioned in the story and could leave the reader wondering what happened, resolve it by the resolution (end) of the story.

7. The theme.

The theme of your story is the take-away value.

Maybe your initial idea is to write a story on bullying, intolerance, or being kind. It could be on mixed families, honoring parents, or sibling rivalry. It could be on anything you feel is important to ‘convey’ to children.

The theme is usually something that will help children in their own lives and should be shown subtly. Don’t try to hit the reader over his head with it.

You may not know the theme when you first start writing, but it should make itself apparent along the way.

8. The ‘feel’ of your story.

The feel of your story is created by three elements: tone, mood, and style.

Tone.

According to The Editor’s Blog, “Tone in fiction is the attitude of the narrator or viewpoint character toward story events and other characters. In a story with first-person POV, tone can also be the narrator’s attitude toward the reader.”

How does the character speak? Is he arrogant, does he curse, is he sarcastic, is he sweet, is he bossy? How he uses his words and sentences will show what attitude the character has.

Word choices and sentence structure create tone. Also, tone can be “altered by the way the viewpoint character or narrator” reacts to the obstacles he’s confronted with. It can also be altered by how he treats the other characters in the story and how he reacts to his surroundings.

Mood.

How you want the reader to feel is established through the story’s mood.

Back to The Editor’s Blog, “Mood can be expressed in terms such as dark, light, rushed, suspenseful, heavy, lighthearted, chaotic, and laid-back.”

The mood of the story should change as the main character goes through his obstacles, especially when the story reaches its climax. The reader should feel apprehension.

If you’ve added humor to the story, the reader should smile and feel lighthearted.

Style.

This is how you use your words to create the story and the story’s feel.

For Walking Through Walls, I chose words and sentences that would fit with 16th-century China. I eliminated contractions from the dialogue. The characters spoke formally and were respectful.

I chose this style based on the period, giving the story an authentic ‘flavor.’

So, it’s easy to see that style is dependent on the story topic.

Every writer has their own unique style, but it can be altered to fit the story’s circumstances.

Say you have a secondary character like “Young Sheldon,” who is in college classes at around ten years old. His speech will differ from that of a boy the same age struggling with fifth-grade reading. Sentence structure and reactions would vary from boy to boy.

Style is used to create tone and mood.

Your story’s tone, style, and mood make it unique to you.

For more on this writing element, check out Tone, Mood, and Style – The Feel of Fiction.

Summing it up.

Wrapping this article up, award-winning author Aaron Shepherd says it best, “The strongest children’s stories have well-developed themes, engaging plots, suitable structure, memorable characters, well-chosen settings, and attractive style. For best results, build strength in all areas.”

So, going back to the very first question in this article, the first step in planning a children’s story is to know what’s involved in creating a good one.

I’m a working children’s ghostwriter, rewriter, editor, and coach. I can help turn your story into a book you’ll be proud to be the author of, one that’s publishable and marketable.

OTHER HELP I OFFER:

HOW TO WRITE A CHILDREN'S FICTION BOOK

A DIY book to help you write your own children’s book.

PICTURE BOOK, CHAPTER BOOK, MIDDLE GRADE BOOK COACHING

Four to ten-week coaching programs.

You can contact me at: kcioffiventrice@gmail.com.

Writing Skills – Spread Your Wings

“Don’t let the enormity of the project stop you—write one page at a time.”

The Author Platform – You Definitely Need One and It Should Have Been Started Yesterday

Successful Writing Strategy – Know Your Intent